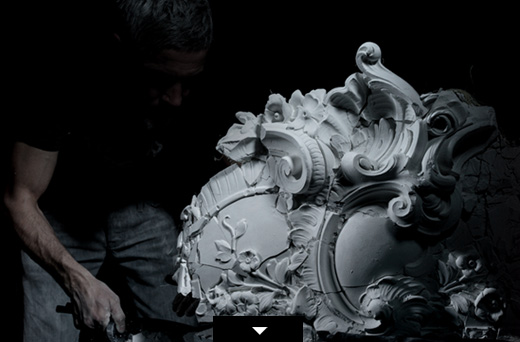

TEMPORARY

SCULPTURES

„The German collective, Flash Lab, peaks playfully beyond that same horizon, using flash to reveal to us phenomena that ordinarily elude human vision.“

complete text

Ben Burbridge

Curator and Deputy Editor, Photoworks

Curator and Deputy Editor, Photoworks

flashlab is an open, multidisciplinary French-German art collective, formed by Olivier Pol Michel, Frank Hoffmann and Jérôme Michel.

They like to share the concept and fuse with other artists to create new creative processes. The first six series were done in collaboartion with Georg Lenz, a photographer from Mainz. The following series were produced in collaboration with Jérome Michel, an architect who lives and works in Paris.

EXHIBITIONS

EXHIBITIONS

Artscout One – Mannheim – 2009 | Kunstverein Mainz – “Hypereal” – 2010

Galerie Art Present – Paris – “Mickeyland” – 2010 | German Aerospace Center – Cologne – 2011 Gallery Spot – Paris – “Cosmos” – 2011 | Gallery Project B – Milan – “Utopia” – 2012

PUBLICATIONS

Photoworks, Edition 14 – 2010 | Komma, Edition 8 – 2011 | Catalogue “Utopia” – 2012 We'd like to say thank you to

ALEXANDER MÜNCH, BEN BURBRIDGE, CHRISTINA STIHLER, CLAUDE BRON, DENNIS JAKOBY, GEORG LENZ, GORDEN MACDONALD, HEINZ PAPST, JOCHEN WEBER, KRISTIN LAUER, KLAUS GERING, LISA STEIN, MARIO-IGNAZIO CIGNA, RALPH HILLERT, RECHER URS, RHEA HÄNI, ROLF LAUTER, SÉBASTIEN SISTEBANE, THOMAS WOLF and VERENA KUNZE

for supporting us and for all the energy and love they share with us.

The exhibits are available in LIMITED EDITIONS,

prices on request. Please send all inquiries per e-mail to: hello@flashlab.de

Follow us on facebook

EXHIBITIONS

EXHIBITIONS

Artscout One – Mannheim – 2009 | Kunstverein Mainz – “Hypereal” – 2010

Galerie Art Present – Paris – “Mickeyland” – 2010 | German Aerospace Center – Cologne – 2011 Gallery Spot – Paris – “Cosmos” – 2011 | Gallery Project B – Milan – “Utopia” – 2012

PUBLICATIONS

Photoworks, Edition 14 – 2010 | Komma, Edition 8 – 2011 | Catalogue “Utopia” – 2012 We'd like to say thank you to

ALEXANDER MÜNCH, BEN BURBRIDGE, CHRISTINA STIHLER, CLAUDE BRON, DENNIS JAKOBY, GEORG LENZ, GORDEN MACDONALD, HEINZ PAPST, JOCHEN WEBER, KRISTIN LAUER, KLAUS GERING, LISA STEIN, MARIO-IGNAZIO CIGNA, RALPH HILLERT, RECHER URS, RHEA HÄNI, ROLF LAUTER, SÉBASTIEN SISTEBANE, THOMAS WOLF and VERENA KUNZE

for supporting us and for all the energy and love they share with us.

The exhibits are available in LIMITED EDITIONS,

prices on request. Please send all inquiries per e-mail to: hello@flashlab.de

Follow us on facebook